Autism vs. OCD: Early Identification Matters

Early identification of OCD in children, whether or not they are also autistic, is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, untreated OCD can significantly impact a child's quality of life, affecting their social interactions, academic performance, and overall well-being. The anxiety and time consumed by obsessions and compulsions can be incredibly disruptive.

AUSTISM SUPPORT

W.Love

4/17/20255 min read

Alright, let's dive into the fascinating intersection of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), especially when it comes to understanding these conditions in early childhood. I am starting this research because my little one is starting to show instances of OCD behavior and I want to get ahead of them and or see if there are ways that I can help my 5 year old.

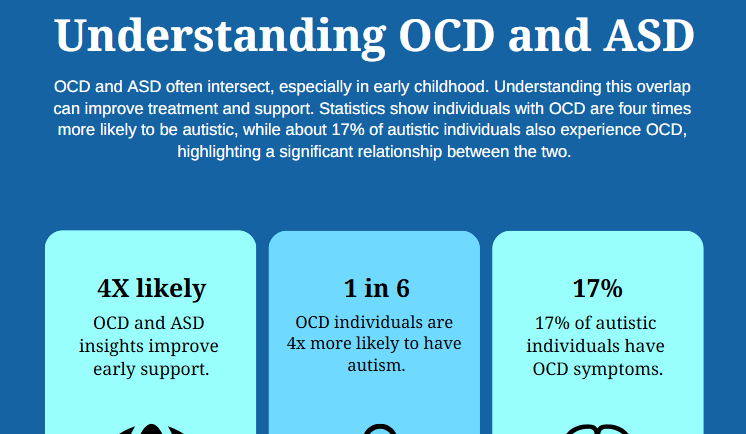

There's a significant overlap between OCD and autism. It highlights some key similarities and differences, and it throws out some pretty interesting statistics. For starters, folks diagnosed with OCD are a whopping 4 times more likely to be autistic.

On the flip side, about 17% of autistic individuals also have OCD. This tells us that while not all autistic people have OCD, and not all people with OCD are autistic, the co-occurrence is definitely something we need to pay attention to.

Why is this important, especially when we're talking about early childhood development? Well, identifying and understanding these conditions early can make a huge difference in providing the right support and interventions. But sometimes, the symptoms can look a bit different in young kids, and the overlap with autism can make diagnosis confusing.

Similarities: Shared Experiences

A few key areas where individuals with OCD and autistic individuals might share similar experiences:

Increased Levels of Compulsions: Both groups can experience increased levels of compulsions. In OCD, compulsions are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that someone feels driven to perform in response to an obsession. Think excessive hand-washing, checking things repeatedly, or counting. Now, in autism, we also see repetitive behaviors, sometimes called stimming (self-stimulatory behaviors). These can include things like hand-flapping, rocking, or repeating words or phrases. While both look like repetitive behaviors, the why behind them can be different. In OCD, it's often about reducing anxiety caused by intrusive thoughts (obsessions). In autism, it can be for self-regulation, sensory input, or a way to express emotions. This distinction is crucial when we're thinking about diagnosing OCD in children, especially those who might also be on the spectrum.

Engagement in Repetitive Behaviors (But Serve Different Purposes): This point really emphasizes the nuance. As we just discussed, both OCD and autism involve repetitive behaviors, but the underlying reasons are often distinct. For a child with OCD, these behaviors are driven by anxiety and the need to neutralize distressing thoughts. For an autistic child, these behaviors might be about seeking sensory input, managing overstimulation, or finding comfort in routine and predictability. Understanding this difference is key for accurate diagnosis and effective support strategies.

Sensory Processing Differences: Both groups often have sensory processing differences. This means they might experience the world around them in a different way when it comes to sights, sounds, textures, tastes, and smells. Some individuals might be hypersensitive (overly sensitive) and find certain stimuli overwhelming, while others might be hyposensitive (under-sensitive) and seek out more intense sensory input. These sensory issues can sometimes contribute to anxiety and repetitive behaviors in both OCD and autism, making it another area where the two conditions can overlap in presentation, particularly in early childhood.

OCD in Early Childhood: What the Research Says

Now, let's bring in some academic perspectives on OCD in early childhood. Research on OCD in young children has shown that it's definitely not just an adult issue. While the way OCD manifests might differ from adults, children as young as preschool age can experience obsessions and compulsions that significantly impact their daily lives.

One key challenge in early childhood OCD is that young children may not have the verbal skills or cognitive awareness to articulate their intrusive thoughts or the reasons behind their compulsions. Their OCD symptoms might present more as observable behaviors. For instance, a young child might repeatedly line up their toys in a very specific way and become extremely distressed if the order is disrupted. This could be a compulsion driven by an obsession about things being "just right" or a fear of something bad happening if they aren't.

Academic sources often discuss the importance of differentiating typical childhood rituals and routines from OCD. Many young children have bedtime routines or preferences for how things are done. However, OCD is characterized by obsessions that cause significant distress and anxiety, and compulsions that are time-consuming and interfere with daily functioning. This level of distress and interference is a key differentiator.

Furthermore, research highlights the potential for early-onset OCD to be associated with other neurodevelopmental conditions, including autism. Studies have explored the genetic and neurological underpinnings of this co-occurrence. Some theories suggest shared vulnerabilities in brain regions involved in executive function, sensory processing, and anxiety regulation.

The Autism Factor: Implications for OCD in Children

When OCD occurs in an autistic child, the presentation can be even more complex. The repetitive behaviors associated with autism might sometimes mask or be mistaken for OCD compulsions. For example, a child who has a strong need for sameness and routine in their autism might also develop OCD related to contamination fears, leading to excessive hand-washing. It can be challenging to tease apart whether the hand-washing is solely driven by OCD or if it's intertwined with their need for predictability and control, which are common in autism.

Academic literature emphasizes the need for careful and comprehensive assessments when evaluating OCD symptoms in autistic children. Standard OCD diagnostic tools might need to be adapted to account for the unique communication styles and behavioral patterns of autistic individuals. Clinicians need to consider the function of the repetitive behaviors – are they primarily anxiety-driven (as in OCD) or more related to sensory needs or a desire for routine (as in autism)?

Why Early Identification Matters

Early identification of OCD in children, whether or not they are also autistic, is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, untreated OCD can significantly impact a child's quality of life, affecting their social interactions, academic performance, and overall well-being. The anxiety and time consumed by obsessions and compulsions can be incredibly disruptive.

Secondly, early intervention with evidence-based treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), particularly Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), can be highly effective in managing OCD symptoms in children. Adapting these therapies to the specific needs of autistic children, who might benefit from more visual supports and structured approaches, is an area of ongoing research and clinical practice.

Finally, understanding the co-occurrence of OCD and autism in early childhood can lead to more tailored and integrated support for families. It allows professionals to address both sets of challenges in a comprehensive way, rather than treating them as separate entities. This might involve collaborating with specialists in both OCD and autism to develop individualized intervention plans.

The heightened likelihood of co-occurrence, the shared experiences of increased compulsions and sensory processing differences, and the crucial distinction in the purpose of repetitive behaviors all underscore the complexity of these conditions.

When we focus on early childhood, the picture becomes even more nuanced. Academic research highlights that OCD can indeed manifest in young children, but its presentation might be different and can be further complicated by the presence of autism. Careful assessment, considering the function of behaviors, and adapting diagnostic and treatment approaches are essential. Early identification and intervention are key to improving the lives of children with OCD, whether they are also autistic or not. By understanding the interplay between these conditions, we can provide more effective and compassionate support to neurodivergent individuals from a young age.

Some sources and related content:

OCD - National Autistic Society